Ten wpis jest również dostępny w języku:

Polski

Hello! 🤟

If you’ve ended up here, you’re probably one of those slightly crazy people who, instead of booking yet another Barcelona trip, start googling: “is there even anything to see in Iraq?”. We did exactly the same. As part of our motorcycle journey from 🇵🇱 Poland to 🇴🇲 Oman we rode through a slice of Federal Iraq – mainly around Baghdad – and this post is all about the places we saw there.

We’ll show you the places we actually saw with our own eyes, plus a few that are still on our “next time” list because, for different reasons (logistics, no local guide, tourist restrictions), we just couldn’t get there. For each spot we’ll add a short “what to expect, what to watch out for, when it’s better to skip it” – because Iraq is not the kind of country where you just wander wherever you want and then get annoyed that something’s closed.

We’re writing this in November 2025, based on what we actually saw in September the same year. Things in this region can change fast, so if you’re reading this later and something already looks different, let us know – we’ll update what we can. Travelling through places like this is a bit of a team sport: people pass on fresh info to each other, and thanks to that it gets a little easier for everyone coming next.

Tourism in Iraq

To give you a bit of context: Iraq as a travel destination is only just waking up. According to the latest data, around 892,000 foreign tourists visited the country in 2024 – that’s roughly 0.1% of all international trips worldwide and puts Iraq around 105th place in global rankings.

At the same time, religious pilgrimage is a completely different story – visits to holy cities like Najaf, Karbala, Kadhimiya and others add up to over 30 million entries a year, with around 6 million of those pilgrims coming from abroad.

Most of that movement comes from the region: pilgrims from Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan and the Gulf. Western travellers are still extremely rare. One report estimated that in 2024 there were only a few hundred tourists from Europe and the Americas combined.

In the Kurdistan Region, though, the numbers are climbing fast – the whole region had around 7 million visitors in 2023, and the Erbil province alone can attract up to 2 million people in just half a year.

So no – Iraq is (not yet) a second Jordan or Türkiye. And that’s exactly why this post exists. If we managed to ride here on a motorbike, you can at least sit back and read what there is to see in and around Baghdad – and where it’s actually worth planning your time, instead of just wandering around the map with no idea where to go.

If you want more of the on-the-ground vibe, 1️⃣ we’ve got a separate post about our stay in Baghdad, and 2️⃣ another one about our earlier days in Erbil, in the Kurdistan Region.

Al-Zawraa Park

ar. متنزه الزوراء / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

We got to Al-Zawraa Park by Careem from our hotel. At the entrance, nobody asked us for money, so to this day we’re not sure if it was some kind of “free entry day” or if they just waved two European tourists through 😊. Normally you should probably expect a small entrance fee of a few hundred dinars per person – more like “fifty cents” than a full-on European theme park ticket.

The park itself is a big green breather in the middle of Baghdad. It used to be a military camp, and only in the 1970s the area was turned into a park of about 3 km², with walking paths, lawns, a lake, a viewing tower and a classic Iraqi-style funfair.

This is not Energylandia level: the rides and rollercoaster feel more “retro” than “wow, what a high-tech miracle”. For local families though, it’s still an important spot – people come here for picnics, walks, to put kids on the rides or just sit by the lake. On weekends the park is supposedly absolutely packed, especially during the flower festival that takes place here in spring.

There’s also a zoo inside the park – one of the oldest in the region. It was hit hard in 2003, when many animals died or escaped during the invasion and the whole place was trashed. Later it was rebuilt and today it’s open again, but newer reviews often mention that some animals look underfed and that conditions in a few enclosures are still far from anything you’d call “European standards”.

Saving Iraqi Culture Monument

ar. نصب انقاذ الثقافة العراقية / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

Just a few minutes’ walk from Al-Zawraa Park there’s something you really can’t ignore: a tall stone cylinder, split open in the middle and held together by hands reaching up from the base.

The monument was designed by famous Baghdad sculptor Mohammed Ghani Hikmat. It was created around 2010 and unveiled a few years later in the Mansour district, on the Karkh side of the city, near Al-Zawraa Park and the fairgrounds.

For Baghdad this monument is almost like a visual shortcut: on one hand it shows how badly wars, looting and decades of chaos have smashed Iraq’s cultural heritage (museums, libraries, historic sites), and on the other it suggests that someone is still trying to hold it all together. It’s no coincidence that it stands by a busy roundabout and a big park rather than hidden inside a museum – it’s meant to be part of everyday city life, something you pass on your way to work or out for a walk.

Victory Arch

ar. قوس الصر / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

The Hands of Victory are probably the most cinematic shot of Baghdad – two gigantic hands holding swords that cross above the avenue. The monument was commissioned by Saddam Hussein after the Iran–Iraq war and unveiled in 1989 as a symbol of Iraq’s “victory” in that conflict. The hands were cast from moulds of Saddam’s own palms, and each sword is about 40 metres long. The arch itself marks the entrance to a huge ceremonial space – the Grand Festivities Square.

The whole thing is located on the grounds of the so-called Green Zone :it all sits inside the Green Zone, the heavily guarded government-and-embassy district in central Baghdad – the same area we wrote about in our main Baghdad article, with lots of military presence, checkpoints and plenty of access restrictions.

And here’s the important part if you want to see it “like a normal person”: you can’t just walk there from Al-Zawraa Park. The only realistic option is to go by car – for example, take a Careem from the nearest checkpoint. Right now the main road through the Green Zone is open to traffic, so you can simply drive under the arch, but the security guys are not too happy about people getting out and wandering around the area.

We did the classic “first-timer mistake”: our driver dropped us literally right next to the arch, we quickly snapped one photo… and a moment later soldiers walked over to check what exactly we were up to. They weren’t aggressive, it was more of a standard check, but the fact is, standing there with a camera under one of the most symbolically sensitive monuments in the Green Zone is not the smartest idea. Looking back, it’s definitely better to take a photo from inside the car, if at all, and not get out unless you have a very clear “ok” from security.

Right next to it stands the Monument to the Unknown Soldier – a massive, slightly futuristic structure from the 1980s, dedicated to fallen Iraqi soldiers. It was designed by Iraqi sculptor Khaled al-Rahal and Italian architect Marcello D’Olivo; there’s even an underground museum beneath the dome. For us, though, it was a hard no on getting inside. We stopped nearby, but the area was closed off and access tightly controlled, so we had to settle for admiring it from a distance.

The arch is part of the Grand Festivities Square mentioned above. It’s a huge parade ground built in the 1980s on the edge of Al-Zawraa Park as the main stage for military parades and state ceremonies. After 2003 the area was pretty much dead for a long time, later partially closed off, but in 2010–2011 the monuments were restored and the space slowly started coming back to life.

Today the Grand Festivities Square is back to hosting big events – festivals, concerts, as well as demonstrations and political rallies.

Baghdad Tower

ar. برج بغداد / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

A slim tower with a dish on top – a bit like a younger cousin of the CN Tower in Canada or the TV tower in Berlin. It was originally called the International Saddam Tower and was built in 1994, after the previous communications tower was destroyed during the Gulf War. It’s about 204 metres tall and was designed with two purposes in mind: as a telecoms hub and as a “people place”, with a revolving restaurant and viewing deck at the top.

After 2003 the tower got a new life and a new name: Baghdad Tower. For years it was used by the US military, then it was renovated, but reopening it to the public has been a very stop-and-go story. Every now and then there’d be announcements about the restaurant and viewing deck opening again, a big event with the lights switched on, official visits from politicians… and then silence. Even as late as 2020 local media and foreign articles were still saying that, despite all the plans, the tower was basically closed in everyday life – a bit of a metaphor for how hard it is to actually finish big projects in Iraq.

The tower sits on the edge of the Green Zone, in the Karkh district, in a heavily guarded area close to key government buildings and the intelligence complex (Harthiya Intelligence Center). Access around it is tightly controlled and the whole area is pretty heavily secured.

Al Rasheed Street

📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

We headed to Al Rasheed in the evening, also on recommendation – a few people messaged us on Instagram saying “you have to go, old Baghdad vibes and Zaza Café”. We got out of the taxi, looked around and our first honest thought was: “wtf, where are we?”. Along the street you’ve got these faded, half-ruined buildings that look like they’ve been waiting for renovation for a few decades, plus weak street lighting, so the whole place gives off a slightly post-apocalyptic vibe.

Only after you walk a bit and get used to the dark does the bigger picture start to make sense. Al Rasheed isn’t just any street – it’s one of the oldest and most important arteries of Baghdad, laid out in the early 20th century under the Ottomans and later named after Caliph Harun al-Rashid. For decades it was the beating heart of the city: cafés, cinemas, bookshops, mosques, meetings of artists and poets, intense political discussions – everything mixed together on one strip.

Then came wars, sanctions and crises, and the street started to fall apart – literally. Collapsed arcades, crumbling facades, shutters pulled down for good. Just a few years ago local media were calling Al Rasheed a “shadow of its former self”, and some of the historic buildings were genuinely at risk of collapsing.

The good news is that from around 2024–2025 things finally started to move. A big revitalisation project kicked off on Al Rasheed – first on the stretch between al-Maidan Square and Ma’ruf al-Rusafi Square. The plan is to restore the facades, tidy up the arcades and even run a tram line down the middle of the street. The first phase of work is close to being finished, and the Iraqi government is proudly saying they want Al Rasheed to become a showcase for the city again, not just a sad “before and after” photo spot.

On the street outside Zaza Café we generally felt safe – every now and then a military patrol drove past or a police car was parked up, people were sitting in the café, someone walked by with shopping bags. The strange part was mostly how dark it gets between the buildings and how brutally you can see the contrast between the street’s former glory and the way it looks now.

Mutanabbi Street

📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

A few minutes’ walk from Zaza Café and you’re in a completely different world. You step into Mutanabbi Street and suddenly – boom, the place is buzzing. Where Al Rasheed felt half-dark and a bit post-apocalyptic, here you’ve got books, people, cafés, kids running around, the smell of tea and cigarettes, conversations coming at you from every direction.

Mutanabbi is Baghdad’s historic book hub – a street that’s been the city’s main “book market” since Abbasid times. Today, less than a kilometre is packed with bookshops and stalls selling second-hand books, school textbooks, poetry, politics, everything you can think of. A lot of sources describe it as “the heart and soul of Baghdad’s intellectual life” – a place where, for decades, writers, poets, students, dissidents and pretty much the whole thinking part of the city have been meeting up.

Right next to it you step into another world: the bazaar. That part is a lot less romantic – tons of cheap Chinese stuff, plastic bits and everyday knick-knacks. For us it was more of a “ok, seen it”, while the book-lined alleys were definitely the part that really stuck in our heads, not the piles of bargain toys.

At the end of the street it’s worth popping into Shabandar Café – one of the most iconic cafés in Iraq. It’s been running since 1917 and has always been a meeting place for writers, politicians and the whole “intellectual” crowd of Baghdad. In 2007 it was almost completely destroyed in a bombing on Mutanabbi Street – over 30 people were killed, including the owner’s four sons and his grandson. Despite that tragedy Shabandar was rebuilt and today it still operates as a symbol of stubborn resilience and the fact that Baghdad’s culture – though badly battered – is still standing.

Al-Kazimiyya Mosque

ar. مسجد ال ياسين / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

We didn’t make it to Kadhimiyah ourselves, but if we had to point to one place in Baghdad that pops up most often in people’s trip reports, it would be this mosque.

It’s the heart of Shia Baghdad: the Al-Kadhimiya Mosque complex (Al-Kadhimayn Shrine) with its huge golden domes and minarets, in the Kadhimiyya district north of the centre. Inside lie two very important Shia imams – Musa al-Kadhim (the 7th imam) and his grandson Muhammad al-Jawad (the 9th imam) – which makes this one of the holiest Shia sites in Iraq, and actually in the whole world. Every year the shrine draws millions of pilgrims from across the country and from abroad.

Architecturally it’s full-on golden overload: two huge gilded domes, four tall minarets (also wrapped in gold), plus glittering tiles, mirrors, calligraphy and a massive courtyard that turns into a sea of people during religious holidays. Travellers often say the same thing in their reports: after walking through the bazaar and security gates you suddenly step into this bright, golden space that just makes you go “wow”.

Security here is very tight: you pass through several layers of checks and metal detectors, walking past police and shrine staff. At a certain point you have to leave your phone and camera before entering the main sanctuary area – there are special lockers and deposit counters for that. Add to this the sheer scale of the crowds: on Fridays and during religious holidays it can get absolutely packed, so moving around feels more like being carried by a river of people than taking a calm stroll through a mosque.

It’s also worth keeping a few things in mind before you go: your outfit has to be as modest as possible – women need their hair covered and loose clothing, and men should wear long trousers and keep their shoulders covered.

Iraqi Martyr Monument

ar. نصب الشهيد العراقي / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

For us this spot played out in a very “Iraqi” way: we rolled up, saw the massive turquoise dome, got all excited about the shot… and then heard there was no entry because “renovation works are underway”. From other travellers’ reports we know this line gets used there a lot and doesn’t always have much to do with any real renovation. Sometimes someone gets in with a local guide, sometimes a group “knows someone inside”, and other times everyone is simply turned back at the gate. We ended up in that last category.

Even from the outside it’s seriously impressive. The Martyrs’ Monument (Al-Shaheed Monument) is one of Baghdad’s most recognisable landmarks. It was built in 1983 as an official memorial to soldiers killed in the Iran–Iraq war, but over time people started to see it more broadly – as a tribute to all Iraqi “martyrs”, no matter which conflict they died in. The monument was designed by sculptor Ismail Fatah al-Turk together with architect Saman Kamal.

In the middle of an artificial lake there’s a circular platform, and on it a huge turquoise-tiled dome, about 40 metres high. The dome is split in half and slightly offset, so from one angle it looks whole, and from another like two open wings. In the gap between them there’s a symbolic flame, and a flagpole with the Iraqi flag rises from the inside. The cut dome is meant to represent the moment of death, the arch opening upwards is the soul’s path, and the water around it is a reminder of the blood spilled in war.

Taq Kisra

ar. طاق كسرى(تیسفون) / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

For us it was a textbook “almost made it” situation. Yet another place where we were told at the entrance that there were conservation works going on, so we couldn’t even take a photo from behind the fence… The next day we see another traveller’s picture in a Facebook group, taken right under the arch, and you just want to throw your hands in the air. In Iraq “renovation” is often a kind of magic password. Sometimes there really is work happening, and sometimes it’s just an easy way to say “no one gets in unless they’re invited”.

Taq Kisra is a surviving fragment of a palace from the time of the Sassanian Empire. The monument stands on the site of the former capital Ctesiphon, in Al-Mada’in, about 30–40 kilometres south of Baghdad, near the town of Salman Pak. What you see today is a massive brick hall with one of the largest unsupported brick arches in the world: around 37 metres high and 25–26 metres wide. It was once the façade of the audience hall, basically the throne “stage” for Persian rulers.

Over the last few decades, Taq Kisra has really had a rough ride. Partial collapses, flooding, unfinished repairs, years of neglect. A major restoration was completed in 2017, but in 2019 and 2020 more sections of the arch fell away, so the whole “how do we save this?” discussion came back in full force. Since then various institutions and foundations have launched rescue projects, but for a regular visitor the reality is simple: officially the site is often “under works” and treated as closed.

On the practical side: navigation apps sometimes try to drag you in via random village roads and a side entrance, which isn’t always the best idea. It’s worth checking the map beforehand to see where the actual main entrance is and where the site boundary starts. If you’re coming from the Al-Salam Bridge side, there’s a checkpoint on the way – just calmly say you’re heading to Taq Kisra and under normal circumstances it’s all good.

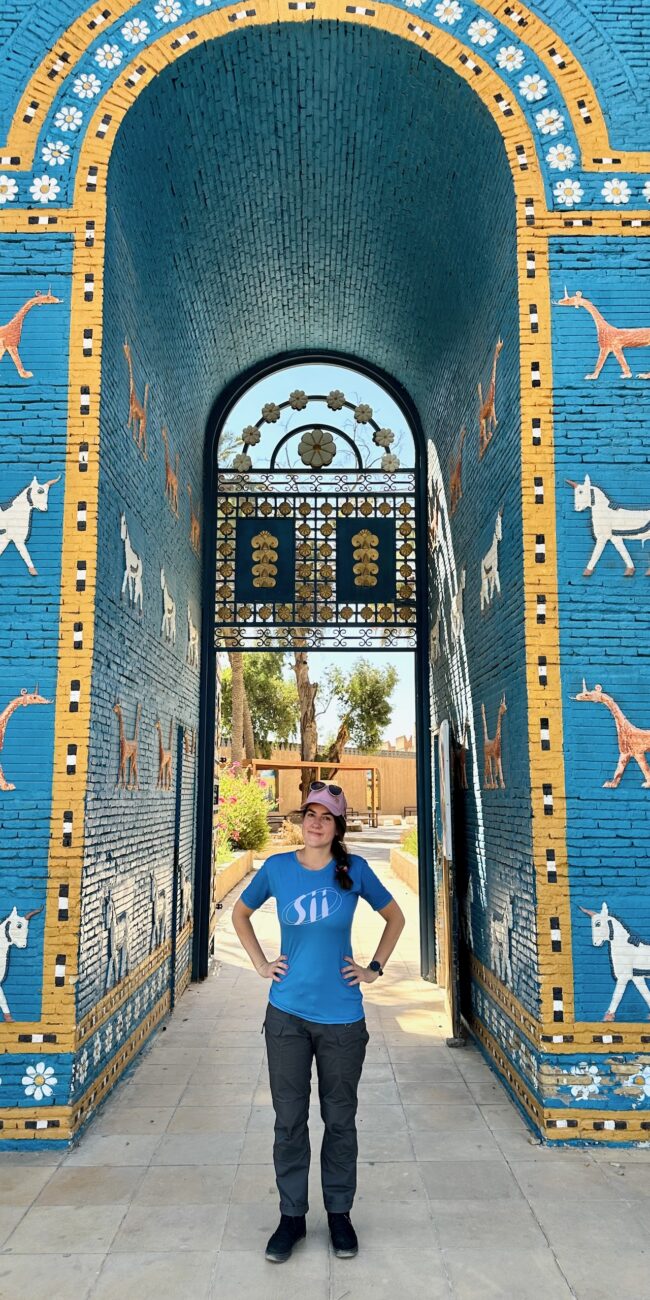

The Ishtar Gate in Babylon

ar. بوابة عشتار / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

If you’ve got your own vehicle or a rental car, getting to Babylon on your own is totally doable. We took Highway 1. The asphalt is more or less fine, but there are ruts and patched sections here and there, so 120 km/h is a sensible max. Then you turn off onto the Hilla–Kish road or, if Waze decides otherwise, earlier onto the quieter Road 8. We ended up with that second option.

That’s where things got interesting. Before entering Babylon Governorate there was a checkpoint where it suddenly got very “warm”. We were asked into some supervisor’s office, our passports disappeared behind a desk and we got the classic “sit, wait”. The guy holding our documents started asking why we’d come, whether we had accommodation, where we’re from, where we work, if we’re YouTubers. For a moment the vibe was pretty suspicious, but once we explained that we were sleeping in Baghdad, didn’t have our stuff with us and just wanted to see Babylon, everything relaxed. In the end it turned out they were more interested in helping us sort things out than grilling us.

It ended with a group photo, bottles of water for the road and a big “welcome in Iraq”. I was drenched in sweat from the stress and 41°C, Jadzia claims she wasn’t scared at all… sure she wasn’t. XD

Entry to the site is paid. For foreigners the current standard is around 25,000 IQD per person, which worked out to roughly 70 PLN for us at the time.

By Iraqi standards that’s quite a lot, especially since you don’t get some huge museum on site, more a vibe of “here are the walls, this is a reconstruction, this is where the palace was”. Oh, and you can pay by card – shocking 😂. When we told the guy at the ticket booth that we were from Poland, he greeted us with a “dzień dobry”. He said there were tons of Poles stationed there during the war and they taught him that 😆.

It didn’t come out of nowhere. After 2003, the ruins and their immediate surroundings were used as “Camp Babylon” – first by US forces, then handed over to Polish command as part of the multinational division. That military presence sadly took a real toll on the archaeological site. Reports from the British Museum and UNESCO openly talk about damaged walls, ground levelled for helipads and heavy vehicles, and other interventions that simply shouldn’t have happened in a place like this.

And the Ishtar Gate you see on site? It’s not the “real one” from the museums in Berlin, but a near full-scale reconstruction built in the 20th century by the Iraqi authorities, based on excavations and the original fragments.

Most of the original ancient bricks with glazed bulls and dragons are now in the Pergamon Museum, while here you get a “new” gate built from blue tiles with recreated reliefs. Even so, when you stand in front of it, it still feels properly impressive.

Today, the entire Babylon complex is a mix of:

- the authentic ruins of the former capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019.

- reconstructions from Saddam Hussein’s era, when a lot of the walls and palaces were “boosted” and rebuilt to look more monumental,

- and traces of the coalition forces’ presence.

Beyond the Ishtar Gate you can walk along the walls, through the reconstructed Processional Way and past the foundations of the old palaces. On some walls you can still spot anti-American slogans left by Iraqis after 2003. There isn’t a dramatic amount of info on site about what’s what, so it’s worth reading up beforehand or finding a decent guide instead of just wandering around aimlessly.

Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Palace in Babylon

ar. قصر العراق في منتجع بابل / 📌 Pin on Google Maps – click here.

Unfortunately, it’s another one of those “no contacts, no entry” spots. We really wanted to get inside – after so many YouTube videos it was begging to be seen with our own eyes. On the ground we got the classic line that the palace was closed for cleaning and conservation works. Classic.

Just to be clear – it’s not like we came here to “admire Saddam”. This is a big, very recent chunk of Iraq’s history, with all the damage and decisions that also affected Babylon itself. The palace stands on an artificially built hill, often called “Saddam Hill”. In the 1980s the village of Qawarish was literally flattened so the dictator could have a residence with a view over the ruins of the ancient city and the Euphrates. The building itself is a bit like a “modern ziggurat”: a massive block with terraces, monumental staircases and interiors full of marble and high ceilings.

After 2003 the palace was taken over by coalition forces. It served as a base for the Americans, and in various reports there are mentions of Polish troops being stationed there too – which is why you can still find traces of the military inside: graffiti, writings on the walls, improvised installations. As of the last few years the structure itself is still standing, but you can clearly see damage and decay, peeling walls, broken details. There have been ideas to turn it into a museum or part of a larger Babylon archaeological centre, but so far it feels more like “plans on paper” than a place that’s actually open to regular visitors.

Summary

Travelling around this country is definitely a challenge – a lot of places are off-limits even for a simple photo, which says a lot about how strongly the authorities still fear for security. On the one hand they really don’t want any incidents, on the other there’s still very little understanding of what tourism is and how natural visitors’ curiosity can be. A good example is that when you enter Iraq overland from Jordan as a foreigner, you may be given a police or military escort “for your own safety”.

We’re not talking mass tourism here, but trying to get to know the history of a country that has been hit by conflict and war almost non-stop for decades.

Sadly, there’s no coherent strategy focused on rebuilding and opening up these sites. Internal political divisions – the push and pull between Shias, Sunnis and Kurds – create chaos and make any kind of “let’s do this together for the country” really hard. The ministry responsible for culture and tourism has often been treated more like a political trophy to hand out between factions than an institution meant to protect heritage, which left it weak and underfunded. The result is that a lot of cultural treasures are slowly falling apart: there isn’t enough money to secure or restore archaeological sites, many museums stay closed, and historic buildings just keep decaying without proper care.

Anyone who comes here needs to know where they’re heading and accept things as they are. Even so, it’s really worth getting to know people on the ground – they’re honest, incredibly welcoming, and even a simple chat (with a phone translator in ręka, if needed) can break a lot of ice and teach you more than jakikolwiek przewodnik. A trip like this really makes you think about life: you can clearly see how the lack of joint action for the country hits not only tourism, but everyday life of ordinary Iraqis.

We left with one big thought in our heads: with a history this rich and people this amazing, Iraq could gain so much if, one day, someone finally managed to build something wspólnie ponad podziałami and really take care of its future.